by Vry4n_ | Aug 26, 2022 | Threat Hunt

Once, the tools have been properly installed. Start analyzing packet captures. For demonstration purposes I will use (https://www.activecountermeasures.com/malware-of-the-day-zeus/)

How to

1. Check the pcap info

2. Parse the pcap file using zeek

- sudo zeek –no-checksums –readfile zeus_1hr.pcap

- ls

Note: As a result we get a lot of log files separated by protocol

3. We can read these log files using less

4. We can use head to grab the column name, and filter the log document using zeek-cut, lets look at conn.log

- head conn.log | grep fields

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.orig_h id.orig_p id.resp_h id.resp_p duration

Note:

id.orig_h = Source IP

id.orig_p = Source port

id.resp_h = Destination IP

id.resp_p = Destination port

duration = session duration

Find long connections

1. Knowing how to filter columns we can proceed to sort them, in order to find long connections, sort by duration

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.orig_h id.orig_p id.resp_h id.resp_p duration | sort -k5rn

2. Now we can remove the “-“ connections and add the time of unique sessions using datamash (sort and datamash work with columns)

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.orig_h id.orig_p id.resp_h id.resp_p duration | sort | grep -v “-” | grep -v “^$” | datamash -g 1,3 sum 5 | sort -k3rn

3. We can also search for multiple unique sessions via http protocol

- cat http.log | zeek-cut id.orig_h id.resp_h | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

4. We can now check the pcap file for requests going to the host that has highest

- sudo ngrep -qI zeus_1hr.pcap “GET /” host 67.207.93.135

Note: We can search for the values in there such as the URI or domain name of the server on the internet to see if there is any association with malware in our case it shows it is part of Zeus malware

5. We can enumerate ports and services

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut service | grep -v “-” | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

6. We can also convert duration to time

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut -d ts

7. We can also filter by column using awk command

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut -d ts id.orig_h id.resp_h service | awk ‘{if($4 != “-” && $4 != “dns”) print $1,$2,$3,$4}’

8. We can check conn.log to filter connections by source and count of sessions

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.orig_h | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

9. We can search for the top destinations

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.resp_h | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

10. Also filter by destination ports

- cat conn.log| zeek-cut id.resp_p | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

Note: Notice uncommon ports are visited more often than known ports such as 80, we can check for duration of the sessions and confirm the flow, in this example we noticed port 9200 has a persistent connection

- cat conn.log | zeek-cut id.orig_h id.resp_h id.resp_p duration | sort -k4rn | head -5

Extra: We can convert that time to seconds

- eval “echo $(date -ud “@$seconds” +’$((%s/3600/24)) days %H hours %M Minutes %S Seconds’)”

Finding beacons ZEEK + RITA (files)

1. After parsing the pcap, we get a file named files.log, reading it using less we can gather the headers

- sudo zeek –no-checksums –readfile zeus_1hr.pcap

- less -Sx20 file.log

2. We can search by filename and its respective hash

- cat files.log | zeek-cut -d ts filename sha1

3. Also, filter by file name to exclude “-“

- cat files.log | zeek-cut filename | grep -iEv “(-)”

4. search by host, destination, protocol, application and filename

- cat files.log | zeek-cut tx_hosts rx_hosts source mime_type filename

5. Filter the results, example, exclude “x509” and iv the column 6 is not equals to “-“

- cat files.log | zeek-cut -d ts tx_hosts rx_hosts source mime_type filename | grep -v ‘x509’ | awk ‘$6!=”-“‘

Finding beacons ZEEK + RITA (DNS)

1. After parsing the pcap, we get a file named dns.log, reading it using less we can gather the headers

- sudo zeek –no-checksums –readfile zeus_1hr.pcap

- less -Sx20 dns.log

2. We can filter all the columns

- cat dns.log| grep fields | awk ‘{ for (i = 1; i <= NF; i++) print $i }’

3. Convert the timestamps to human readable

- cat dns.log | zeek-cut -d ts

4. We can filter by source, destination IPs & DNS query

- cat dns.log | zeek-cut -d ts id.resp_h id.dest_h query

5. We can use grep to get rid of the domain local queries, or legit queries that we see, | is used as “or”

- cat dns.log | zeek-cut -d ts id.resp_h id.dest_h query | grep -iEv ‘(desktop-)’

- cat dns.log | zeek-cut -d ts id.resp_h id.dest_h query | grep -iEv ‘(desktop-|in-addr.arpa)’

Using RITA to import logs into database

1. Import the .log files

- sudo rita import . malware_db

2. Once, the data has been imported we can search by beacons

- sudo rita show-beacons malware_db –human-readable

3. This can be printed in html format

- sudo rita html-report malware_db

4. Search for an interesting IP and list the files where it appears

5. Search within a specific log

- grep -iR 67.207.93.135 conn.log

by Vry4n_ | Aug 26, 2022 | Threat Hunt

RITA is an open source framework for network traffic analysis. The framework ingests Zeek Logs in TSV format, and currently supports the following major features:

- Beaconing Detection: Search for signs of beaconing behavior in and out of your network

- DNS Tunneling Detection Search for signs of DNS based covert channels

- Blacklist Checking: Query blacklists to search for suspicious domains and hosts

https://github.com/activecm/rita

Note: RITA needs Zeek logs as input, and, MongoDB to build a database

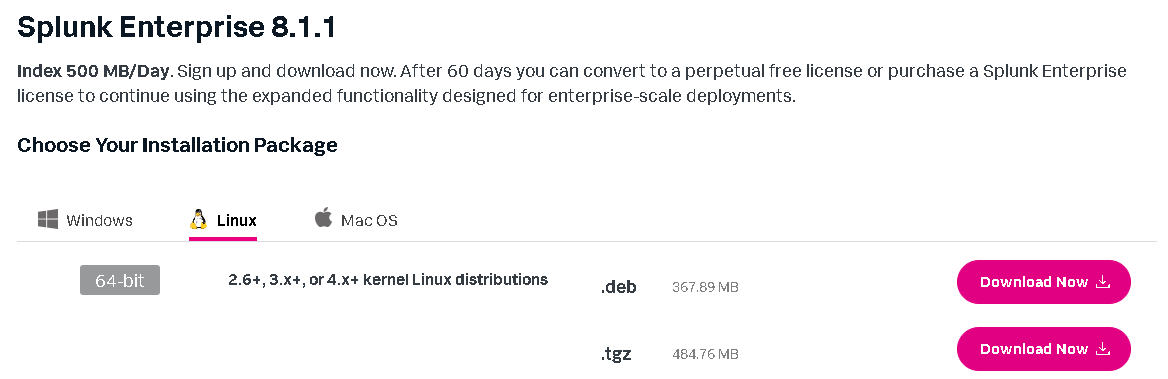

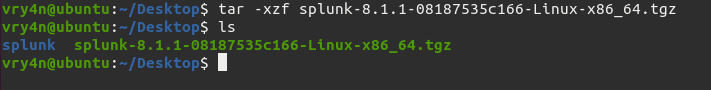

How to set Up

Using the manual installation process (https://github.com/activecm/rita/blob/master/docs/Manual%20Installation.md)

MongoDB

MongoDB is a high-performance, open source, schema-free document-oriented data store that’s easy to deploy, manage and use. It’s network accessible, written in C++ and offers

the following features:

- Collection oriented storage – easy storage of object-style data

- Full index support, including on inner objects

- Query profiling

- Replication and fail-over support

- Efficient storage of binary data including large objects (e.g. videos)

- Auto-sharding for cloud-level scalability

1. Follow the steps below as indicated in GitHub

2. Check the vendor documentation (https://www.mongodb.com/docs/v4.2/installation/)

3. Follow the steps indicated in “Install MongoDB Community Edition” section, Import the public key used by the package management system. We should get “OK” as response

- wget -qO – https://www.mongodb.org/static/pgp/server-4.2.asc | sudo apt-key add –

Note: if you receive an error indicating that gnupg is not installed, you can

- sudo apt-get install gnupg

4. Create a /etc/apt/sources.list.d/mongodb-org-4.2.list file for MongoDB.

- echo “deb http://repo.mongodb.org/apt/debian buster/mongodb-org/4.2 main” | sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/mongodb-org-4.2.list

5. Issue the following command to reload the local package database:

6. Install the MongoDB packages.

- sudo apt-get install -y mongodb-org

7. Start MongoDB

- sudo systemctl start mongod

- sudo systemctl status mongod

Note: If you receive an error similar to the following when starting mongod:

- Failed to start mongod.service: Unit mongod.service not found.

Run the following command first:

- sudo systemctl daemon-reload

8. (OPTIONAL) You can ensure that MongoDB will start following a system reboot by issuing the following command:

- sudo systemctl enable mongod

9. Stop/Restart MongoDB

- sudo systemctl stop mongod

- sudo systemctl restart mongod

RITA

1. Follow the steps below as indicated in GitHub (https://github.com/activecm/rita/blob/master/docs/Manual%20Installation.md)

2. Download the RITA binaries

3. Compile the files using “make” & “make install” commands

- sudo make

- sudo make install

4. Now that it successfully compiled and installed, we can run rita as test

5. RITA requires a few directories to be created for it to function correctly.

- sudo mkdir /etc/rita && sudo chmod 755 /etc/rita

- sudo mkdir -p /var/lib/rita/logs && sudo chmod -R 755 /var/lib/rita

6. Copy the config file from your local RITA source code.

- sudo cp etc/rita.yaml /etc/rita/config.yaml && sudo chmod 666 /etc/rita/config.yaml

7. Using RITA again we don’t get the config.yaml error

8. Test the config

ZEEK

Zeek is primarily a security monitor that inspects all traffic on a link in depth for signs of suspicious activity.

1. Follow the steps below as indicated in GitHub (https://github.com/activecm/rita/blob/master/docs/Manual%20Installation.md)

2. Visit Zeek documentation

3. Make sure that you meet the pre-requisites, if you don’t or don’t know, scroll down and find “To install the required dependencies, you can use:” section, I’ll use Debian’s dependencies installation

- sudo apt-get install cmake make gcc g++ flex bison libpcap-dev libssl-dev python3 python3-dev swig zlib1g-dev -y

4. Now install Zeek

5. Check zeek has been installed

6. We now need to get zeek-cut tool, which is very important to manage the pcap. Visit https://github.com/zeek

7. Now proceed to download the zeek-aux code (https://github.com/zeek/zeek-aux) to install “zeek-cut” command. zeek-cut extracts the given columns from ASCII Zeek logs on standard input, and outputs

them to standard output.

8. Now, we need to compile these binaries, for this we will need “cmake” which can be found in https://github.com/zeek/cmake, download the files within the zeek-aux folder

Note: This is a collection of CMake scripts intended to be included as a

git submodule in other repositories related to Zeek

9. Now run it

- sudo ./configure

- sudo make

- sudo make install

- sudo updated

10. In order to locate the executable use

- locate zeek-cut

- file /usr/local/zeek/bin/zeek-cut

- sudo cp /usr/local/zeek/bin/zeek-cut /usr/bin

11. Verify zeek-cut can be now run as a command

Cheat sheet

The tool is ready to use. Here you have some ZEEK commands that you can use (https://github.com/corelight/bro-cheatsheets)

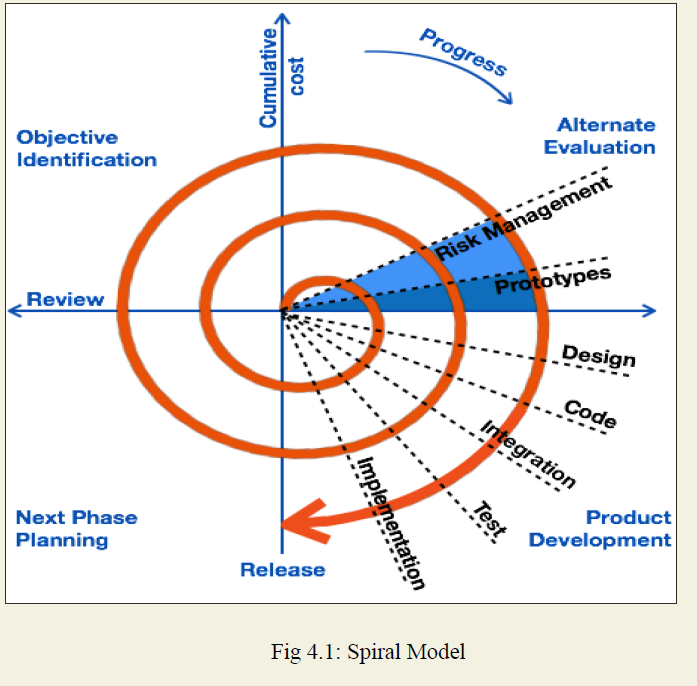

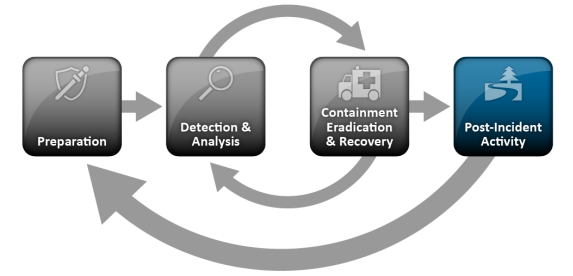

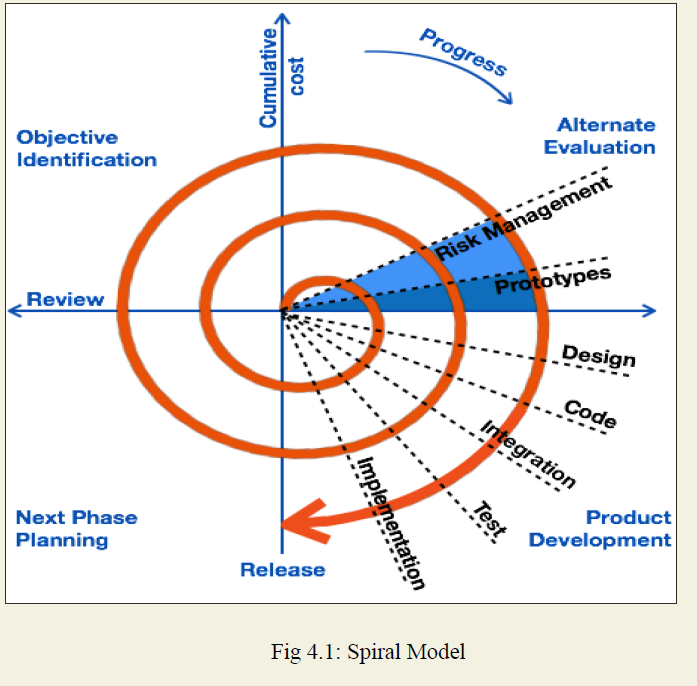

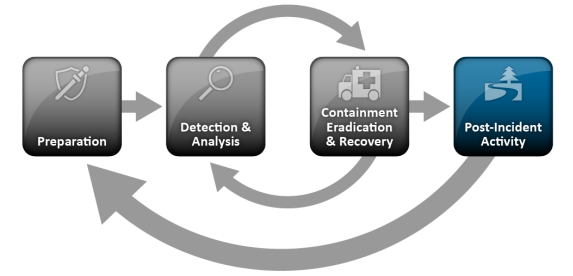

by Vry4n_ | Dec 30, 2020 | Incident Response

The incident response process has several phases. The initial phase involves establishing and training an incident response team, and acquiring the necessary tools and resources.

Summary of every phase in Incident response life cycle

1. Preparation

This phase will be the work horse of your incident response planning, and in the end, the most crucial phase to protect your business. Part of this phase includes:

- Ensure your employees are properly trained regarding their incident response roles and responsibilities in the event of data breach

- Develop incident response drill scenarios and regularly conduct mock data breaches to evaluate your incident response plan.

- Ensure that all aspects of your incident response plan (training, execution, hardware and software resources, etc.) are approved and funded in advance

- Your response plan should be well documented, thoroughly explaining everyone’s roles and responsibilities. Then the plan must be tested in order to assure that your employees will perform as they were trained. The more prepared your employees are, the less likely they’ll make critical mistakes.

Questions to address

- Has everyone been trained on security policies?

- Have your security policies and incident response plan been approved by appropriate management?

- Does the Incident Response Team know their roles and the required notifications to make?

- Have all Incident Response Team members participated in mock drills?

2. Identification

This is the process where you determine whether you’ve been breached. A breach, or incident, could originate from many different areas.

Questions to address

- When did the event happen?

- How was it discovered?

- Who discovered it?

- Have any other areas been impacted?

- What is the scope of the compromise?

- Does it affect operations?

- Has the source (point of entry) of the event been discovered?

3. Containment

When a breach is first discovered, your initial instinct may be to securely delete everything so you can just get rid of it. However, that will likely hurt you in the long run since you’ll be destroying valuable evidence that you need to determine where the breach started and devise a plan to prevent it from happening again.

Instead, contain the breach so it doesn’t spread and cause further damage to your business. If you can, disconnect affected devices from the Internet. Have short-term and long-term containment strategies ready. It’s also good to have a redundant system back-up to help restore business operations. That way, any compromised data isn’t lost forever.

This is also a good time to update and patch your systems, review your remote access protocols (requiring mandatory multi-factor authentication), change all user and administrative access credentials and harden all passwords.

Questions to address

- What’s been done to contain the breach short term?

- What’s been done to contain the breach long term?

- Has any discovered malware been quarantined from the rest of the environment?

- What sort of backups are in place?

- Does your remote access require true multi-factor authentication?

- Have all access credentials been reviewed for legitimacy, hardened and changed?

- Have you applied all recent security patches and updates?

4. Eradication

Once you’ve contained the issue, you need to find and eliminate the root cause of the breach. This means all malware should be securely removed, systems should again be hardened and patched, and updates should be applied.

Whether you do this yourself, or hire a third party to do it, you need to be thorough. If any trace of malware or security issues remain in your systems, you may still be losing valuable data, and your liability could increase.

Questions to address

- Have artifacts/malware from the attacker been securely removed?

- Has the system be hardened, patched, and updates applied?

- Can the system be re-imaged?

5. Recovery

This is the process of restoring and returning affected systems and devices back into your business environment. During this time, it’s important to get your systems and business operations up and running again without the fear of another breach.

Questions to address

- When can systems be returned to production?

- Have systems been patched, hardened and tested?

- Can the system be restored from a trusted back-up?

- How long will the affected systems be monitored and what will you look for when monitoring?

- What tools will ensure similar attacks will not reoccur? (File integrity monitoring, intrusion detection/protection, etc)

6. Lessons Learned

Once the investigation is complete, hold an after-action meeting with all Incident Response Team members and discuss what you’ve learned from the data breach. This is where you will analyze and document everything about the breach. Determine what worked well in your response plan, and where there were some holes. Lessons learned from both mock and real events will help strengthen your systems against the future attacks.

Questions to address

- What changes need to be made to the security?

- How should employee be trained differently?

- What weakness did the breach exploit?

- How will you ensure a similar breach doesn’t happen again?

Each phase deeply explained

Preparation

Incident response methodologies typically emphasize preparation—not only establishing an incident response capability so that the organization is ready to respond to incidents, but also preventing incidents by ensuring that systems, networks, and applications are sufficiently secure. Although the incident response team is not typically responsible for incident prevention, it is fundamental to the success of incident response programs.

Preparing to Handle Incidents

The lists below provide examples of tools and resources available that may be of value during incident handling. These lists are intended to be a starting point for discussions about which tools and resources an organization’s incident handlers need

Incident Handler Communications and Facilities

- Contact information for team members and others within and outside the organization (primary and backup contacts), such as law enforcement and other incident response teams; information may include phone numbers, email addresses, public encryption keys (in accordance with the encryption software described below), and instructions for verifying the contact’s identity

- On-call information for other teams within the organization, including escalation information

- Incident reporting mechanisms, such as phone numbers, email addresses, online forms, and secure instant messaging systems that users can use to report suspected incidents; at least one mechanism should permit people to report incidents anonymously

- Issue tracking system for tracking incident information, status, etc

- Smartphones to be carried by team members for off-hour support and onsite communications

- Encryption software to be used for communications among team members, within the organization and with external parties; for Federal agencies, software must use a FIPS-validated encryption algorithm

- War room for central communication and coordination; if a permanent war room is not necessary or practical, the team should create a procedure for procuring a temporary war room when needed

- Secure storage facility for securing evidence and other sensitive materials

Incident Analysis Hardware and Software

- Digital forensic workstations21 and/or backup devices to create disk images, preserve log files, and save other relevant incident data

- Laptops for activities such as analyzing data, sniffing packets, and writing reports

- Spare workstations, servers, and networking equipment, or the virtualized equivalents, which may be used for many purposes, such as restoring backups and trying out malware

- Blank removable media

- Portable printer to print copies of log files and other evidence from non-networked systems Packet sniffers and protocol analyzers to capture and analyze network traffic

- Digital forensic software to analyze disk images

- Removable media with trusted versions of programs to be used to gather evidence from systems

- Evidence gathering accessories, including hard-bound notebooks, digital cameras, audio recorders, chain of custody forms, evidence storage bags and tags, and evidence tape, to preserve evidence for possible legal actions

Incident Analysis Resources

- Port lists, including commonly used ports and Trojan horse ports

- Documentation for OSs, applications, protocols, and intrusion detection and antivirus products

- Network diagrams and lists of critical assets, such as database servers

- Current baselines of expected network, system, and application activity

- Cryptographic hashes of critical files22 to speed incident analysis, verification, and eradication

Incident Mitigation Software

- Access to images of clean OS and application installations for restoration and recovery purposes

- Many incident response teams create a jump kit, which is a portable case that contains materials that may be needed during an investigation. The jump kit should be ready to go at all times. Jump kits contain many of the same items listed in the bulleted lists above. Each jump kit typically includes a laptop, loaded with appropriate software

- Each incident handler should have access to at least two computing devices (e.g., laptops). One, such as the one from the jump kit, should be used to perform packet sniffing, malware analysis, and all other actions that risk contaminating the laptop that performs them, each incident handler should also have a standard laptop, smart phone, or other computing device for writing reports, reading email, and performing other duties unrelated to the hands-on incident analysis.

Preventing Incidents

The following provides a brief overview of some of the main recommended practices for securing networks, systems, and applications

- Risk Assessments. Periodic risk assessments of systems and applications should determine what risks are posed by combinations of threats and vulnerabilities. This should include understanding the applicable threats, including organization-specific threats. Each risk should be prioritized, and the risks can be mitigated, transferred, or accepted until a reasonable overall level of risk is reached. Another benefit of conducting risk assessments regularly is that critical resources are identified, allowing staff to emphasize monitoring and response activities for those resources.

- Host Security. All hosts should be hardened appropriately using standard configurations. In addition to keeping each host properly patched, hosts should be configured to follow the principle of least privilege—granting users only the privileges necessary for performing their authorized tasks. Hosts should have auditing enabled and should log significant security-related events. The security of hosts and their configurations should be continuously monitored. Many organizations use Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP) expressed operating system and application configuration checklists to assist in securing hosts consistently and effectively.

- Network Security. The network perimeter should be configured to deny all activity that is not expressly permitted. This includes securing all connection points, such as virtual private networks (VPNs) and dedicated connections to other organizations.

- Malware Prevention. Software to detect and stop malware should be deployed throughout the organization. Malware protection should be deployed at the host level (e.g., server and workstation operating systems), the application server level (e.g., email server, web proxies), and the application client level (e.g., email clients, instant messaging clients).

- User Awareness and Training. Users should be made aware of policies and procedures regarding appropriate use of networks, systems, and applications. Applicable lessons learned from previous incidents should also be shared with users so they can see how their actions could affect the organization. Improving user awareness regarding incidents should reduce the frequency of incidents. IT staff should be trained so that they can maintain their networks, systems, and applications in accordance with the organization’s security standards

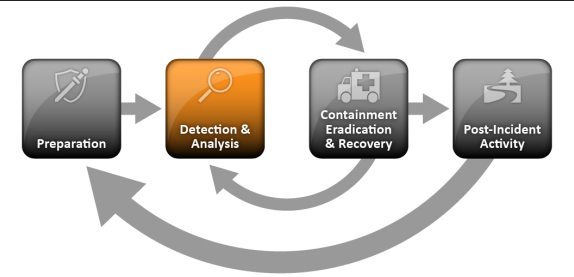

Detection and Analysis

Attack Vectors

Incidents can occur in countless ways, so it is infeasible to develop step-by-step instructions for handling every incident. Organizations should be generally prepared to handle any incident but should focus on being prepared to handle incidents that use common attack vectors. Different types of incidents merit different response strategies.

- External/Removable Media: An attack executed from removable media or a peripheral device—for example, malicious code spreading onto a system from an infected USB flash drive.

- Attrition: An attack that employs brute force methods to compromise, degrade, or destroy systems, networks, or services (e.g., a DDoS intended to impair or deny access to a service or application; a brute force attack against an authentication mechanism, such as passwords, CAPTCHAS, or digital signatures).

- Web: An attack executed from a website or web-based application—for example, a cross-site scripting attack used to steal credentials or a redirect to a site that exploits a browser vulnerability and installs malware.

- Email: An attack executed via an email message or attachment—for example, exploit code disguised as an attached document or a link to a malicious website in the body of an email message.

- Impersonation: An attack involving replacement of something benign with something malicious— for example, spoofing, man in the middle attacks, rogue wireless access points, and SQL injection attacks all involve impersonation.

- Improper Usage: Any incident resulting from violation of an organization’s acceptable usage policies by an authorized user, excluding the above categories; for example, a user installs file sharing software, leading to the loss of sensitive data; or a user performs illegal activities on a system.

- Loss or Theft of Equipment: The loss or theft of a computing device or media used by the organization, such as a laptop, smartphone, or authentication token.

- Other: An attack that does not fit into any of the other categories

Signs of an Incident

The most challenging part of the incident response process is accurately detecting and assessing possible incidents—determining whether an incident has occurred and, if so, the type, extent, and magnitude of the problem.

- Incidents may be detected through many different means, with varying levels of detail and fidelity. Automated detection capabilities include network-based and host-based IDPSs, antivirus software, and log analyzers. Incidents may also be detected through manual means, such as problems reported by users. Some incidents have overt signs that can be easily detected, whereas others are almost impossible to detect.

- The volume of potential signs of incidents is typically high—for example, it is not uncommon for an organization to receive thousands or even millions of intrusion detection sensor alerts per day. (See Section 3.2.4 for information on analyzing such alerts.)

- Deep, specialized technical knowledge and extensive experience are necessary for proper and efficient analysis of incident-related data.

Signs of an incident fall into one of two categories: precursors and indicators

- A precursor is a sign that an incident may occur in the future.

- Web server log entries that show the usage of a vulnerability scanner

- An announcement of a new exploit that targets a vulnerability of the organization’s mail server

- A threat from a group stating that the group will attack the organization

- An indicator is a sign that an incident may have occurred or may be occurring now.

- A network intrusion detection sensor alerts when a buffer overflow attempt occurs against a database server.

- Antivirus software alerts when it detects that a host is infected with malware.

- A system administrator sees a filename with unusual characters.

- A host records an auditing configuration change in its log

- An application logs multiple failed login attempts from an unfamiliar remote system.

- An email administrator sees a large number of bounced emails with suspicious content.

- A network administrator notices an unusual deviation from typical network traffic flows.

Sources of Precursors and Indicators

Precursors and indicators are identified using many different sources, with the most common being computer security software alerts, logs, publicly available information, and people

| Source |

Description |

| Alerts |

| IDPSs |

IDPS products identify suspicious events and record pertinent data regarding them, including the date and time the attack was detected, the type of attack, the source and destination IP addresses, and the username (if applicable and known). Most IDPS products use attack signatures to identify malicious activity; the signatures must be kept up to date so that the newest attacks can be detected. IDPS software often produces false positives—alerts that indicate malicious activity is occurring, when in fact there has been none. Analysts should manually validate IDPS alerts either by closely reviewing the recorded supporting data or by getting related data from other sources |

| SIEMs |

Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) products are similar to IDPS products, but they generate alerts based on analysis of log data |

| Antivirus and antispam software |

Antivirus software detects various forms of malware, generates alerts, and prevents the malware from infecting hosts. Current antivirus products are effective at stopping many instances of malware if their signatures are kept up to date. Antispam software is used to detect spam and prevent it from reaching users’ mailboxes. Spam may contain malware, phishing attacks, and other malicious content, so alerts from antispam software may indicate attack attempts. |

| File integrity checking software |

File integrity checking software can detect changes made to important files during incidents. It uses a hashing algorithm to obtain a cryptographic checksum for each designated file. If the file is altered and the checksum is recalculated, an extremely high probability exists that the new checksum will not match the old checksum. By regularly recalculating checksums and comparing them with previous values, changes to files can be detected |

| Third-party monitoring services |

Third parties offer a variety of subscription-based and free monitoring services. An example is fraud detection services that will notify an organization if its IP addresses, domain names, etc. are associated with current incident activity involving other organizations. There are also free real-time blacklists with similar information. Another example of a third-party monitoring service is a CSIRC notification list; these lists are often available only to other incident response teams |

| Source |

Description |

| Logs |

| Operating system, service and application logs |

Logs from operating systems, services, and applications (particularly audit-related data) are frequently of great value when an incident occurs, such as recording which accounts were accessed and what actions were performed. Organizations should require a baseline level of logging on all systems and a higher baseline level on critical systems. Logs can be used for analysis by correlating event information. Depending on the event information, an alert can be generated to indicate an incident. |

| Network device logs |

Logs from network devices such as firewalls and routers are not typically a primary source of precursors or indicators. Although these devices are usually configured to log blocked connection attempts, they provide little information about the nature of the activity. Still, they can be valuable in identifying network trends and in correlating events detected by other devices |

| Network flows |

A network flow is a particular communication session occurring between hosts. Routers and other networking devices can provide network flow information, which can be used to find anomalous network activity caused by malware, data exfiltration, and other malicious acts. There are many standards for flow data formats, including NetFlow, sFlow, and IPFIX. |

| Source |

Description |

| Publicly Available Information |

| Information on new vulnerabilities and exploits |

Keeping up with new vulnerabilities and exploits can prevent some incidents from occurring and assist in detecting and analyzing new attacks. The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) contains information on vulnerabilities. Organizations such as US-CERT33 and CERT® /CC periodically provide threat update information through briefings, web postings, and mailing lists. |

| Source |

Description |

| People |

| People from within the organization |

Users, system administrators, network administrators, security staff, and others from within the organization may report signs of incidents. It is important to validate all such reports. One approach is to ask people who provide such information how confident they are of the accuracy of the information. Recording this estimate along with the information provided can help considerably during incident analysis, particularly when conflicting data is discovered. |

| People from other organizations |

Reports of incidents that originate externally should be taken seriously. For example, the organization might be contacted by a party claiming a system at the organization is attacking its systems. External users may also report other indicators, such as a defaced web page or an unavailable service. Other incident response teams also may report incidents. It is important to have mechanisms in place for external parties to report indicators and for trained staff to monitor those mechanisms carefully; this may be as simple as setting up a phone number and email address, configured to forward messages to the help desk. |

Incident Analysis

Incident detection and analysis would be easy if every precursor or indicator were guaranteed to be accurate; unfortunately, this is not the case.

- user-provided indicators such as a complaint of a server being unavailable are often incorrect.

- Intrusion detection systems may produce false positives

Even if an indicator is accurate, it does not necessarily mean that an incident has occurred. Some indicators, such as a server crash or modification of critical files, could happen for several reasons other than a security incident, including human error

- Determining whether a particular event is actually an incident is sometimes a matter of judgment. It may be necessary to collaborate with other technical and information security personnel to make a decision

- The best remedy is to build a team of highly experienced and proficient staff members who can analyze the precursors and indicators effectively and efficiently and take appropriate actions. Without a well-trained and capable staff, incident detection and analysis will be conducted inefficiently, and costly mistakes will be made.

When the team believes that an incident has occurred, the team should rapidly perform an initial analysis to determine the incident’s scope, such as

- which networks, systems, or applications are affected

- who or what originated the incident

- how the incident is occurring (e.g., what tools or attack methods are being used, what vulnerabilities are being exploited).

Recommendations for making incident analysis easier and more effective

- Profile Networks and Systems. Profiling is measuring the characteristics of expected activity so that changes to it can be more easily identified. Examples of profiling are running file integrity checking software on hosts to derive checksums for critical files and monitoring network bandwidth usage to determine what the average and peak usage levels are on various days and times. In practice, it is difficult to detect incidents accurately using most profiling techniques; organizations should use profiling as one of several detection and analysis techniques.

- Understand Normal Behaviors. Incident response team members should study networks, systems, and applications to understand what their normal behavior is so that abnormal behavior can be recognized more easily. No incident handler will have a comprehensive knowledge of all behavior throughout the environment, but handlers should know which experts could fill in the gaps. One way to gain this knowledge is through reviewing log entries and security alerts. This may be tedious if filtering is not used to condense the logs to a reasonable size. As handlers become more familiar with the logs and alerts, they should be able to focus on unexplained entries, which are usually more important to investigate. Conducting frequent log reviews should keep the knowledge fresh, and the analyst should be able to notice trends and changes over time. The reviews also give the analyst an indication of the reliability of each source.

- Create a Log Retention Policy. Information regarding an incident may be recorded in several places, such as firewall, IDPS, and application logs. Creating and implementing a log retention policy that specifies how long log data should be maintained may be extremely helpful in analysis because older log entries may show reconnaissance activity or previous instances of similar attacks. Another reason for retaining logs is that incidents may not be discovered until days, weeks, or even months later. The length of time to maintain log data is dependent on several factors, including the organization’s data retention policies and the volume of data.

- Perform Event Correlation. Evidence of an incident may be captured in several logs that each contain different types of data—a firewall log may have the source IP address that was used, whereas an application log may contain a username. A network IDPS may detect that an attack was launched against a particular host, but it may not know if the attack was successful. The analyst may need to examine the host’s logs to determine that information. Correlating events among multiple indicator sources can be invaluable in validating whether a particular incident occurred.

- Keep All Host Clocks Synchronized. Protocols such as the Network Time Protocol (NTP) synchronize clocks among hosts. Event correlation will be more complicated if the devices reporting events have inconsistent clock settings. From an evidentiary standpoint, it is preferable to have consistent timestamps in logs—for example, to have three logs that show an attack occurred at 12:07:01 a.m., rather than logs that list the attack as occurring at 12:07:01, 12:10:35, and 11:07:06.

- Maintain and Use a Knowledge Base of Information. The knowledge base should include information that handlers need for referencing quickly during incident analysis. Although it is possible to build a knowledge base with a complex structure, a simple approach can be effective. Text documents, spreadsheets, and relatively simple databases provide effective, flexible, and searchable mechanisms for sharing data among team members. The knowledge base should also contain a variety of information, including explanations of the significance and validity of precursors and indicators, such as IDPS alerts, operating system log entries, and application error codes.

- Use Internet Search Engines for Research. Internet search engines can help analysts find information on unusual activity. For example, an analyst may see some unusual connection attempts targeting TCP port 22912. Performing a search on the terms “TCP,” “port,” and “22912” may return some hits that contain logs of similar activity or even an explanation of the significance of the port number. Note that separate workstations should be used for research to minimize the risk to the organization from conducting these searches.

- Run Packet Sniffers to Collect Additional Data. Sometimes the indicators do not record enough detail to permit the handler to understand what is occurring. If an incident is occurring over a network, the fastest way to collect the necessary data may be to have a packet sniffer capture network traffic. Configuring the sniffer to record traffic that matches specified criteria should keep the volume of data manageable and minimize the inadvertent capture of other information. Because of privacy concerns, some organizations may require incident handlers to request and receive permission before using packet sniffers.

- Filter the Data. There is simply not enough time to review and analyze all the indicators; at minimum the most suspicious activity should be investigated. One effective strategy is to filter out categories of indicators that tend to be insignificant. Another filtering strategy is to show only the categories of indicators that are of the highest significance; however, this approach carries substantial risk because new malicious activity may not fall into one of the chosen indicator categories

- Seek Assistance from Others. Occasionally, the team will be unable to determine the full cause and nature of an incident. If the team lacks sufficient information to contain and eradicate the incident, then it should consult with internal resources (e.g., information security staff) and external resources (e.g., US-CERT, other CSIRTs, contractors with incident response expertise). It is important to accurately determine the cause of each incident so that it can be fully contained and the exploited vulnerabilities can be mitigated to prevent similar incidents from occurring.

Incident Documentation

Documenting system events, conversations, and observed changes in files can lead to a more efficient, more systematic, and less errorprone handling of the problem.

- Every step taken from the time the incident was detected to its final resolution should be documented and timestamped.

- Every document regarding the incident should be dated and signed by the incident handler

- Information of this nature can also be used as evidence in a court of law if legal prosecution is pursued.

- Whenever possible, handlers should work in teams of at least two: one person can record and log events while the other person performs the technical tasks.

Using an application or a database, such as an issue tracking system, helps ensure that incidents are handled and resolved in a timely manner. The issue tracking system should contain information on the following:

- The current status of the incident (new, in progress, forwarded for investigation, resolved, etc.)

- A summary of the incident

- Indicators related to the incident

- Other incidents related to this incident

- Actions taken by all incident handlers on this incident

- Chain of custody, if applicable

- Impact assessments related to the incident

- Contact information for other involved parties (e.g., system owners, system administrators)

- A list of evidence gathered during the incident investigation

- Comments from incident handlers

- Next steps to be taken (e.g., rebuild the host, upgrade an application).

Incident Prioritization

Prioritizing the handling of the incident is perhaps the most critical decision point in the incident handling process.

- Functional Impact of the Incident. Incidents targeting IT systems typically impact the business functionality that those systems provide, resulting in some type of negative impact to the users of those systems. Incident handlers should consider how the incident will impact the existing functionality of the affected systems. Incident handlers should consider not only the current functional impact of the incident, but also the likely future functional impact of the incident if it is not immediately contained.

| Category |

Definition |

| None |

No effect to the organization’s ability to provide all services to all users |

| Low |

Minimal effect; the organization can still provide all critical services to all users but has lost efficiency |

| Medium |

Organization has lost the ability to provide a critical service to a subset of system users |

| High |

Organization is no longer able to provide some critical services to any users |

- Information Impact of the Incident. Incidents may affect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the organization’s information. For example, a malicious agent may exfiltrate sensitive information. Incident handlers should consider how this information exfiltration will impact the organization’s overall mission. An incident that results in the exfiltration of sensitive information may also affect other organizations if any of the data pertained to a partner organization.

| Category |

Definition |

| None |

No information was exfiltrated, changed, deleted, or otherwise compromised |

| Privacy Breach |

Sensitive personally identifiable information (PII) of taxpayers, employees, beneficiaries, etc. was accessed or exfiltrated |

| Proprietary Breach |

Unclassified proprietary information, such as protected critical infrastructure information (PCII), was accessed or exfiltrated |

| Integrity Loss |

Sensitive or proprietary information was changed or deleted |

- Recoverability from the Incident. The size of the incident and the type of resources it affects will determine the amount of time and resources that must be spent on recovering from that incident. In some instances it is not possible to recover from an incident (e.g., if the confidentiality of sensitive information has been compromised) and it would not make sense to spend limited resources on an elongated incident handling cycle, unless that effort was directed at ensuring that a similar incident did not occur in the future. In other cases, an incident may require far more resources to handle than what an organization has available. Incident handlers should consider the effort necessary to actually recover from an incident and carefully weigh that against the value the recovery effort will create and any requirements related to incident handling.

| Category |

Definition |

| Regular |

Time to recovery is predictable with existing resources |

| Supplemented |

Time to recovery is predictable with additional resources |

| Extended |

Time to recovery is unpredictable; additional resources and outside help are needed |

| Not Recoverable |

Recovery from the incident is not possible (e.g., sensitive data exfiltrated and posted publicly); launch investigation |

Combining the functional impact to the organization’s systems and the impact to the organization’s information determines the business impact of the incident.

The recoverability from the incident determines the possible responses that the team may take when handling the incident. An incident with a high functional impact and low effort to recover from is an ideal candidate for immediate action from the team.

Organizations should also establish an escalation process for those instances when the team does not respond to an incident within the designated time.

- The escalation process should state how long a person should wait for a response and what to do if no response occurs

- Generally, the first step is to duplicate the initial contact. After waiting for a brief time—perhaps 15 minutes—the caller should escalate the incident to a higher level, such as the incident response team manager.

- If that person does not respond within a certain time, then the incident should be escalated again to a higher level of management.

- This process should be repeated until someone responds.

Incident Notification

When an incident is analyzed and prioritized, the incident response team needs to notify the appropriate individuals so that all who need to be involved will play their roles. The exact reporting requirements vary among organizations, but parties that are typically notified include:

- CIO

- Head of information security

- Local information security officer

- Other incident response teams within the organization

- External incident response teams (if appropriate)

- System owner

- Human resources (for cases involving employees, such as harassment through email)

- Public affairs (for incidents that may generate publicity)

- Legal department (for incidents with potential legal ramifications)

- US-CERT (required for Federal agencies and systems operated on behalf of the Federal government)

- Law enforcement (if appropriate)

During incident handling, the team may need to provide status updates to certain parties, even in some cases the entire organization. The team should plan and prepare several communication methods, including out-of-band methods (e.g., in person, paper), and select the methods that are appropriate for a particular incident. Possible communication methods include:

- Email

- Website (internal, external, or portal)

- Telephone calls

- In person (e.g., daily briefings)

- Voice mailbox greeting (e.g., set up a separate voice mailbox for incident updates, and update the greeting message to reflect the current incident status; use the help desk’s voice mail greeting)

- Paper (e.g., post notices on bulletin boards and doors, hand out notices at all entrance points).

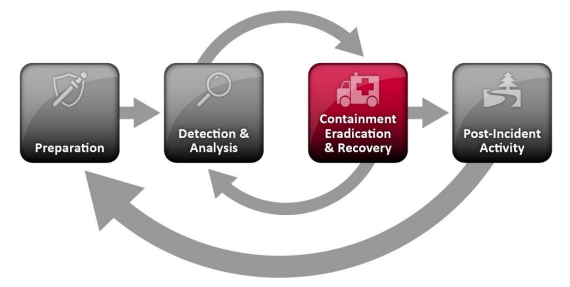

Containment, Eradication, and Recovery

Choosing a Containment Strategy

Containment is important before an incident overwhelms resources or increases damage. Most incidents require containment, so that is an important consideration early in the course of handling each incident.

- Containment provides time for developing a tailored remediation strategy

- An essential part of containment is decision-making (e.g., shut down a system, disconnect it from a network, disable certain functions).

Organizations should create separate containment strategies for each major incident type, with criteria documented clearly to facilitate decision-making. Criteria for determining the appropriate strategy include:

- Potential damage to and theft of resources

- Need for evidence preservation

- Service availability (e.g., network connectivity, services provided to external parties)

- Time and resources needed to implement the strategy

- Effectiveness of the strategy (e.g., partial containment, full containment)

- Duration of the solution (e.g., emergency workaround to be removed in four hours, temporary workaround to be removed in two weeks, permanent solution)

In certain cases, some organizations redirect the attacker to a sandbox (a form of containment) so that they can monitor the attacker’s activity, usually to gather additional evidence.

Evidence Gathering and Handling

Although the primary reason for gathering evidence during an incident is to resolve the incident, it may also be needed for legal proceedings.

- it is important to clearly document how all evidence, including compromised systems, has been preserved

- Evidence should be collected according to procedures that meet all applicable laws and regulations that have been developed from previous discussions with legal staff and appropriate law enforcement agencies so that any evidence can be admissible in court

- In addition, evidence should be accounted for at all times; whenever evidence is transferred from person to person, chain of custody forms should detail the transfer and include each party’s signature

A detailed log should be kept for all evidence, including the following:

- Identifying information (e.g., the location, serial number, model number, hostname, media access control (MAC) addresses, and IP addresses of a computer)

- Name, title, and phone number of each individual who collected or handled the evidence during the investigation

- Time and date (including time zone) of each occurrence of evidence handling

- Locations where the evidence was stored.

Collecting evidence from computing resources presents some challenges. It is generally desirable to acquire evidence from a system of interest as soon as one suspects that an incident may have occurred. Many incidents cause a dynamic chain of events to occur; an initial system snapshot may do more good in identifying the problem and its source than most other actions that can be taken at this stage

Identifying the Attacking Hosts

The following items describe the most commonly performed activities for attacking host identification:

- Validating the Attacking Host’s IP Address. New incident handlers often focus on the attacking host’s IP address. The handler may attempt to validate that the address was not spoofed by verifying connectivity to it; however, this simply indicates that a host at that address does or does not respond to the requests.

- Researching the Attacking Host through Search Engines. Performing an Internet search using the apparent source IP address of an attack may lead to more information on the attack.

- Using Incident Databases. Several groups collect and consolidate incident data from various organizations into incident databases. This information sharing may take place in many forms, such as trackers and real-time blacklists. The organization can also check its own knowledge base or issue tracking system for related activity.

- Monitoring Possible Attacker Communication Channels. Incident handlers can monitor communication channels that may be used by an attacking host. For example, many bots use IRC as their primary means of communication. Also, attackers may congregate on certain IRC channels to brag about their compromises and share information. However, incident handlers should treat any such information that they acquire only as a potential lead, not as fact

Eradication and Recovery

Eradication

After an incident has been contained, eradication may be necessary to:

- Eliminate components of the incident, such as deleting malware and disabling breached user accounts

- Identifying and mitigating all vulnerabilities that were exploited

- It is important to identify all affected hosts within the organization so that they can be remediated.

Recovery

Recovery may involve such actions as

- administrators restore systems to normal operation,

- confirm that the systems are functioning normally

- (if applicable) remediate vulnerabilities to prevent similar incidents

- restoring systems from clean backups or rebuilding systems from scratch

- replacing compromised files with clean versions

- Installing patches

- changing passwords

- A tightening network perimeter security (e.g., firewall rulesets, boundary router access control lists)

- Higher levels of system logging or network monitoring are often part of the recovery process

Eradication and recovery should be done in a phased approach so that remediation steps are prioritized. For large-scale incidents, recovery may take months; the intent of the early phases should be to increase the overall security with relatively quick (days to weeks) high value changes to prevent future incidents.

Post-Incident Activity

Lessons Learned

Each incident response team should evolve to reflect new threats, improved technology, and lessons learned. Holding a “lessons learned” meeting with all involved parties after a major incident, and optionally periodically after lesser incidents as resources permit, can be extremely helpful in improving security measures and the incident handling process itself. Questions to be answered in the meeting include:

- what occurred

- what was done to intervene

- how well intervention worked

- Exactly what happened, and at what times?

- How well did staff and management perform in dealing with the incident? Were the documented procedures followed? Were they adequate?

- What information was needed sooner?

- Were any steps or actions taken that might have inhibited the recovery?

- What would the staff and management do differently the next time a similar incident occurs?

- How could information sharing with other organizations have been improved?

- What corrective actions can prevent similar incidents in the future?

- What precursors or indicators should be watched for in the future to detect similar incidents?

- What additional tools or resources are needed to detect, analyze, and mitigate future incidents?

Meeting handling

- Small incidents need limited post-incident analysis, with the exception of incidents performed through new attack methods that are of widespread concern and interest.

- After serious attacks have occurred, it is usually worthwhile to hold post-mortem meetings that cross team and organizational boundaries to provide a mechanism for information sharing.

- The primary consideration in holding such meetings is ensuring that the right people are involved. Not only is it important to invite people who have been involved in the incident that is being analyzed, but also it is wise to consider who should be invited for the purpose of facilitating future cooperation.

- The success of such meetings also depends on the agenda

- Collecting input about expectations and needs (including suggested topics to cover) from participants before the meeting increases the likelihood that the participants’ needs will be met.

- In addition, establishing rules of order before or during the start of a meeting can minimize confusion and discord.

- Having one or more moderators who are skilled in group facilitation can yield a high payoff

- it is also important to document the major points of agreement and action items and to communicate them to parties who could not attend the meeting

Benefits from having post-activity meetings

- Reports from these lessons learned meetings are good material for training new team members by showing them how more experienced team members respond to incidents

- Updating incident response policies and procedures is another important part of the lessons learned process

- Post-mortem analysis of the way an incident was handled will often reveal a missing step or an inaccuracy in a procedure, providing impetus for change.

- Creating a follow-up report for each incident, which can be quite valuable for future use.

- Creating a formal chronology of events (including timestamped information such as log data from systems) is important for legal reasons, as is creating a monetary estimate of the amount of damage the incident caused.

Using Collected Incident Data

Organizations should focus on collecting data that is actionable, rather than collecting data simply because it is available

- The data, particularly the total hours of involvement and the cost, may be used to justify additional funding of the incident response team.

- A study of incident characteristics may indicate systemic security weaknesses and threats, as well as changes in incident trends.

- Measuring the success of the incident response team

- Determine if a change to incident response capabilities causes a corresponding change in the team’s performance (e.g., improvements in efficiency, reductions in costs).

Possible metrics for incident-related data include:

- Number of Incidents Handled. The number of incidents handled is best taken as a measure of the relative amount of work that the incident response team had to perform, not as a measure of the quality of the team, unless it is considered in the context of other measures that collectively give an indication of work quality.

- It is more effective to produce separate incident counts for each incident category. Subcategories also can be used to provide more information.

- Time Per Incident. For each incident, time can be measured in several ways:

- Total amount of labor spent working on the incident

- Elapsed time from the beginning of the incident to incident discovery, to the initial impact assessment, and to each stage of the incident handling process (e.g., containment, recovery)

- How long it took the incident response team to respond to the initial report of the incident

- How long it took to report the incident to management and, if necessary, appropriate external entities (e.g., US-CERT).

- Objective Assessment of Each Incident. The response to an incident that has been resolved can be analyzed to determine how effective it was. The following are examples of performing an objective assessment of an incident

- Reviewing logs, forms, reports, and other incident documentation for adherence to established incident response policies and procedures

- Identifying which precursors and indicators of the incident were recorded to determine how effectively the incident was logged and identified

- Determining if the incident caused damage before it was detected

- Determining if the actual cause of the incident was identified, and identifying the vector of attack, the vulnerabilities exploited, and the characteristics of the targeted or victimized systems, networks, and applications

- Determining if the incident is a recurrence of a previous incident

- Calculating the estimated monetary damage from the incident (e.g., information and critical business processes negatively affected by the incident)

- Measuring the difference between the initial impact assessment and the final impact assessment

- Identifying which measures, if any, could have prevented the incident.

- Subjective Assessment of Each Incident. Incident response team members may be asked to assess their own performance, as well as that of other team members and of the entire team. Another valuable source of input is the owner of a resource that was attacked, in order to determine if the owner thinks the incident was handled efficiently and if the outcome was satisfactory.

Besides using these metrics to measure the team’s success, organizations may also find it useful to periodically audit their incident response programs. Audits will identify problems and deficiencies that can then be corrected. At a minimum, an incident response audit should evaluate the following items against applicable regulations, policies, and generally accepted practices:

- Incident response policies, plans, and procedures

- Tools and resources

- Team model and structure

- Incident handler training and education

- Incident documentation and reports

- The measures of success discussed earlier in this section

Evidence Retention

Organizations should establish policy for how long evidence from an incident should be retained. Most organizations choose to retain all evidence for months or years after the incident ends. The following factors should be considered during the policy creation:

- Prosecution. If it is possible that the attacker will be prosecuted, evidence may need to be retained until all legal actions have been completed. In some cases, this may take several years. Furthermore, evidence that seems insignificant now may become more important in the future.

- For example, if an attacker is able to use knowledge gathered in one attack to perform a more severe attack later, evidence from the first attack may be key to explaining how the second attack was accomplished

- Data Retention. Most organizations have data retention policies that state how long certain types of data may be kept.

- For example, an organization may state that email messages should be retained for only 180 days.

- If a disk image contains thousands of emails, the organization may not want the image to be kept for more than 180 days unless it is absolutely necessary.

- Cost. Original hardware (e.g., hard drives, compromised systems) that is stored as evidence, as well as hard drives and removable media that are used to hold disk images, are generally individually inexpensive. However, if an organization stores many such components for years, the cost can be substantial. The organization also must retain functional computers that can use the stored hardware and media.

Incident Handling Checklist

The checklist provides guidelines to handlers on the major steps that should be performed; it does not dictate the exact sequence of steps that should always be followed.

| Action |

Completed |

| Detection and Analysis |

| 1. |

Determine whether an incident has occurred |

|

| 1.1 |

Analyze the precursors and indicators |

|

| 1.2 |

Look for correlating information |

|

| 1.3 |

Perform research (e.g., search engines, knowledge base) |

|

| 1.4 |

As soon as the handler believes an incident has occurred, begin documenting the investigation and gathering evidence |

|

| 2. |

Prioritize handling the incident based on the relevant factors (functional impact, information impact, recoverability effort, etc.) |

|

| 3. |

Report the incident to the appropriate internal personnel and external organizations |

|

| Containment, Eradication, and Recovery |

| 4. |

Acquire, preserve, secure, and document evidence |

|

| 5. |

Contain the incident |

|

| 6. |

Eradicate the incident |

|

| 6.1 |

Identify and mitigate all vulnerabilities that were exploited |

|

| 6.2 |

Remove malware, inappropriate materials, and other components |

|

| 6.3 |

If more affected hosts are discovered (e.g., new malware infections), repeat the Detection and Analysis steps (1.1, 1.2) to identify all other affected hosts, then contain (5) and eradicate (6) the incident for them |

|

| 7. |

Recover from the incident |

|

| 7.1 |

Return affected systems to an operationally ready state |

|

| 7.2 |

Confirm that the affected systems are functioning normally |

|

| 7.3 |

If necessary, implement additional monitoring to look for future related activity |

|

| Post-Incident Activity |

| 8. |

Create a follow-up report |

|

| 9. |

Hold a lessons learned meeting (mandatory for major incidents, optional otherwise) |

|

Recommendations

- Acquire tools and resources that may be of value during incident handling. The team will be more efficient at handling incidents if various tools and resources are already available to them. Examples include contact lists, encryption software, network diagrams, backup devices, digital forensic software, and port lists.

- Prevent incidents from occurring by ensuring that networks, systems, and applications are sufficiently secure. Preventing incidents is beneficial to the organization and also reduces the workload of the incident response team. Performing periodic risk assessments and reducing the identified risks to an acceptable level are effective in reducing the number of incidents. Awareness of security policies and procedures by users, IT staff, and management is also very important.

- Identify precursors and indicators through alerts generated by several types of security software. Intrusion detection and prevention systems, antivirus software, and file integrity checking software are valuable for detecting signs of incidents. Each type of software may detect incidents that the other types of software cannot, so the use of several types of computer security software is highly recommended. Third-party monitoring services can also be helpful.

- Establish mechanisms for outside parties to report incidents. Outside parties may want to report incidents to the organization—for example, they may believe that one of the organization’s users is attacking them. Organizations should publish a phone number and email address that outside parties can use to report such incidents.

- Require a baseline level of logging and auditing on all systems, and a higher baseline level on all critical systems. Logs from operating systems, services, and applications frequently provide value during incident analysis, particularly if auditing was enabled. The logs can provide information such as which accounts were accessed and what actions were performed.

- Profile networks and systems. Profiling measures the characteristics of expected activity levels so that changes in patterns can be more easily identified. If the profiling process is automated, deviations from expected activity levels can be detected and reported to administrators quickly, leading to faster detection of incidents and operational issues.

- Understand the normal behaviors of networks, systems, and applications. Team members who understand normal behavior should be able to recognize abnormal behavior more easily. This knowledge can best be gained by reviewing log entries and security alerts; the handlers should become familiar with the typical data and can investigate the unusual entries to gain more knowledge.

- Create a log retention policy. Information regarding an incident may be recorded in several places. Creating and implementing a log retention policy that specifies how long log data should be maintained may be extremely helpful in analysis because older log entries may show reconnaissance activity or previous instances of similar attacks.

- Perform event correlation. Evidence of an incident may be captured in several logs. Correlating events among multiple sources can be invaluable in collecting all the available information for an incident and validating whether the incident occurred.

- Keep all host clocks synchronized. If the devices reporting events have inconsistent clock settings, event correlation will be more complicated. Clock discrepancies may also cause issues from an evidentiary standpoint.

- Maintain and use a knowledge base of information. Handlers need to reference information quickly during incident analysis; a centralized knowledge base provides a consistent, maintainable source of information. The knowledge base should include general information, such as data on precursors and indicators of previous incidents.

- Start recording all information as soon as the team suspects that an incident has occurred. Every step taken, from the time the incident was detected to its final resolution, should be documented and timestamped. Information of this nature can serve as evidence in a court of law if legal prosecution is pursued. Recording the steps performed can also lead to a more efficient, systematic, and less error-prone handling of the problem.

- Safeguard incident data. It often contains sensitive information regarding such things as vulnerabilities, security breaches, and users that may have performed inappropriate actions. The team should ensure that access to incident data is restricted properly, both logically and physically.

- Prioritize handling of the incidents based on the relevant factors. Because of resource limitations, incidents should not be handled on a first-come, first-served basis. Instead, organizations should establish written guidelines that outline how quickly the team must respond to the incident and what actions should be performed, based on relevant factors such as the functional and information impact of the incident, and the likely recoverability from the incident. This saves time for the incident handlers and provides a justification to management and system owners for their actions. Organizations should also establish an escalation process for those instances when the team does not respond to an incident within the designated time.

- Include provisions regarding incident reporting in the organization’s incident response policy. Organizations should specify which incidents must be reported, when they must be reported, and to whom. The parties most commonly notified are the CIO, head of information security, local information security officer, other incident response teams within the organization, and system owners.

- Establish strategies and procedures for containing incidents. It is important to contain incidents quickly and effectively to limit their business impact. Organizations should define acceptable risks in containing incidents and develop strategies and procedures accordingly. Containment strategies should vary based on the type of incident.

- Follow established procedures for evidence gathering and handling. The team should clearly document how all evidence has been preserved. Evidence should be accounted for at all times. The team should meet with legal staff and law enforcement agencies to discuss evidence handling, then develop procedures based on those discussions.

- Capture volatile data from systems as evidence. This includes lists of network connections, processes, login sessions, open files, network interface configurations, and the contents of memory. Running carefully chosen commands from trusted media can collect the necessary information without damaging the system’s evidence.

- Obtain system snapshots through full forensic disk images, not file system backups. Disk images should be made to sanitized write-protectable or write-once media. This process is superior to a file system backup for investigatory and evidentiary purposes. Imaging is also valuable in that it is much safer to analyze an image than it is to perform analysis on the original system because the analysis may inadvertently alter the original.

- Hold lessons learned meetings after major incidents. Lessons learned meetings are extremely helpful in improving security measures and the incident handling process itself.

by Vry4n_ | Dec 29, 2020 | Incident Response

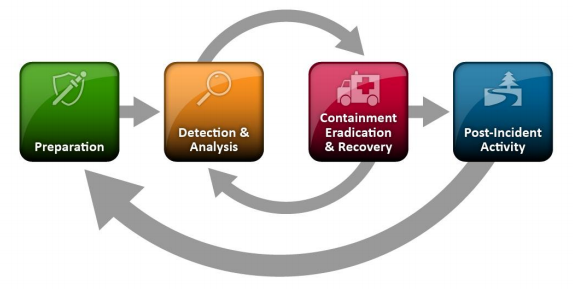

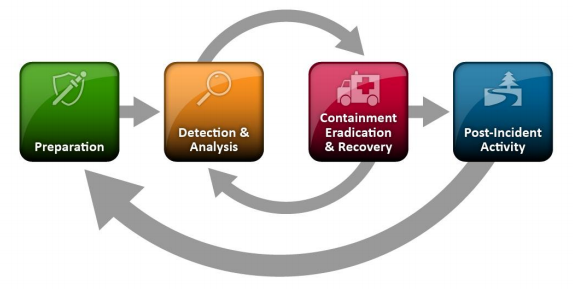

Incident response is a structured process organizations use to identify and deal with cybersecurity incidents. Response includes several stages, including preparation for incidents, detection and analysis of a security incident, containment, eradication, and full recovery, and post-incident analysis and learning.

This post is a shorter summary of NIST official documentation. (https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-61r2.pdf)

Establishing an incident response capability should include the following actions:

- Creating an incident response policy and plan

- Developing procedures for performing incident handling and reporting

- Setting guidelines for communicating with outside parties regarding incidents

- Selecting a team structure and staffing model

- Establishing relationships and lines of communication between the incident response team and other

- groups, both internal (e.g., legal department) and external (e.g., law enforcement agencies)

- Determining what services, the incident response team should provide

- Staffing and training the incident response team

Organizations should reduce the frequency of incidents by effectively securing networks, systems, and applications.

Preventing problems is often less costly and more effective than reacting to them after they occur. Thus,

incident prevention is an important complement to an incident response capability. Incident handling can be performed more effectively if organizations complement their incident response capability with adequate resources to actively maintain the security of networks, systems, and applications. This includes training IT staff on complying with the organization’s security standards and making users aware of policies and procedures regarding appropriate use of networks, systems, and applications.

Organizations should document their guidelines for interactions with other organizations regarding incidents.

During incident handling, the organization will need to communicate with outside parties, such as other

incident response teams, law enforcement, the media, vendors, and victim organizations. Because these

communications often need to occur quickly, organizations should predetermine communication

guidelines so that only the appropriate information is shared with the right parties.

Organizations should be generally prepared to handle any incident but should focus on being prepared to handle incidents that use common attack vectors

Incidents can occur in countless ways, so it is infeasible to develop step-by-step instructions for handling every incident. This publication defines several types of incidents, based on common attack vectors. Different types of incidents merit different response strategies

What is the difference between an attack vector, attack surface and data breach?

- Attack vector: A method or way an attacker can gain unauthorized access to a network or computer system.

- Attack surface: The total number of attack vectors an attacker can use to manipulate a network or computer system or extract data.

- Data breach: Any security incident where sensitive, protected, or confidential data is accessed or stolen by an unauthorized party.

The attack vectors are:

- External/Removable Media: An attack executed from removable media (e.g., flash drive, CD) or a peripheral device.

- Attrition: An attack that employs brute force methods to compromise, degrade, or destroy systems, networks, or services.

- Web: An attack executed from a website or web-based application.

- Email: An attack executed via an email message or attachment.

- Improper Usage: Any incident resulting from violation of an organization’s acceptable usage policies by an authorized user, excluding the above categories.

- Loss or Theft of Equipment: The loss or theft of a computing device or media used by the organization, such as a laptop or smartphone.

- Other: An attack that does not fit into any of the other categories.

Organizations should emphasize the importance of incident detection and analysis throughout the organization.

Organizations should establish logging standards and procedures to ensure that adequate information is collected by logs and security software and that the data is reviewed regularly.

Automation is needed to perform an initial analysis of the data and select events of interest for human review. Event correlation software can be of great value in automating the analysis process. However, the effectiveness of the process depends on the quality of the data that goes into it.

Organizations should create written guidelines for prioritizing incidents.

Incidents should be prioritized based on the relevant factors, such as

- the functional impact of the incident (effect on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the organization’s information).

- the information impact of the incident (effect on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the organization’s information)

- the recoverability from the incident (the time and types of resources that must be spent on recovering from the incident)

Organizations should use the lessons learned process to gain value from incidents